Stories to Tell - With a little help...

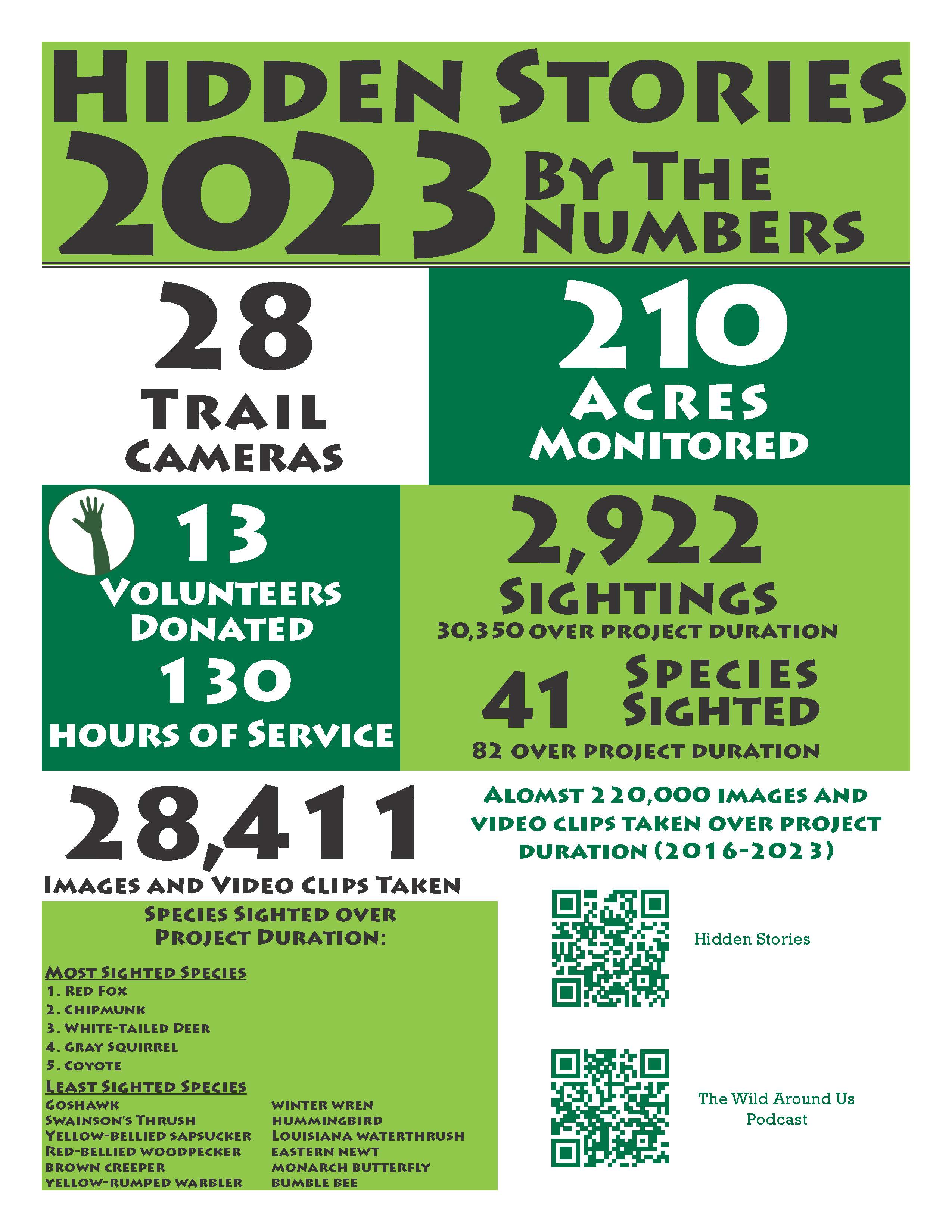

The growth of the trail camera project has required some changes to the process. Thirty cameras are spread throughout 210 acres in a variety of natural communities; forests, fields, ponds, streams, and vernal pools. This provides insight into what animals are in the area and how they are using the landscape, but it also requires time to visit each location and change out the camera card on a routine basis. How can one person monitor all this? The simple answer is you can’t. A small group of volunteers is trained to help us monitor the cameras and collect cards to be uploaded into a database. They are invaluable in being the eyes and ears on the ground replacing drained batteries, noting animal sign in the vicinity, and the status of each camera. With their help, the project has been able to expand its breadth and depth of coverage.

Humans have not been the only ones to help-out with the project. Some animals have also “helped” in their own ways. Two examples come to mind. One occurred early in the summer of 2018 in one of the field locations that can see a lot of activity. This location usually shows most animal activity between dusk and dawn. A volunteer noted that this camera’s batteries were completely drained, although they had been at 99% two weeks earlier. I wondered if the batteries were bad, the camera was having its own problem, or there were a lot of visitors who happened to walk past this location. I uploaded the information from the camera to find nearly 12,000 images! I started going through images and found that the majority of images were false triggers. There was no wildlife or people, just the landscape around the camera. This was happening every two or three seconds during the day but at night the camera responded normally, triggering when animals walked by. What could be triggering it during the day? Sometimes movement of vegetation by wind causes false triggers, but upon review of the images there was no sign of wind. My third clue came when I noticed small dark blots on the images that appeared to move. I was puzzled and it wasn’t until I could make out legs on either side of the dark blots, that I realized we had ants on and in the camera. A colony of ants thought the inside of the camera was an ideal location to “set up house”. Their constant activity of walking across the sensor caused all the blank images. I cleaned the ants out of the camera and had it back and working in a few days. Without the help of our volunteer, we would have lost a lot more camera time monitoring that site.

Sometimes however, animal interference can actually provide a new opportunity. On two separate occasions, black bear have taken it upon themselves to change the camera’s focus to a different part of the forest. Mainly the ground.

Black bear are curious and investigate new objects that capture their attention. The first sense they use to explore new situations is their nose. If they are still curious, they might use their paws next. In this case a female bear smelled the camera, deemed it was not worth any more of her time and left, but the cub had different ideas.

T:\Trail Cameras\Video-for-use\Bear-repos.mp4

I was surprised to discover the bear’s actions created an opportunity to look at the natural areas from a different perspective. Although the scope of the surroundings the camera captured was limited, it provided a different perspective than normally seen. By focusing the camera on the forest floor we recorded new wildlife species including a shrew, a red-backed vole, and a hermit thrush.

T:\Trail Cameras\Video-for-use\Shrew-RBvole.mp4

T:\Trail Cameras\Video-for-use\Hermit-thrush.mp4

The cameras also caught close up footage of other animals that we’ve seen more often, mice, chipmunks, and squirrels.

As our human volunteers continue to help monitor the cameras throughout the year, our “wildlife volunteers” may add their own touches to the process. Now if we can just work on their composition and focusing skills.

You don’t need a game camera to discover the wildlife stories that occur in an area. If you’re lucky, and happen to be in the right place at the right time, a story unfolds before your eyes. This happened to me in mid-May as I walked along the marsh boardwalk. The water of the pond was calm and still. Pollen from some of the early blooming trees lay upon the surface as a gauzy, white film. The light from the early morning sun in the clear sky made it a natural spot to pause for a moment.

A flash of white below the surface caught my eye. I looked more closely and recognized the light skin of a snapping turtle’s neck and forelegs. The mottled brown shell was covered with a green film of algae and its brown dinosaur-like tail blended into the bed of bladderwort it was suspended above. The turtle’s shell was twelve to fourteen inches long, a good-sized turtle for a small pond. It slowly began to swim, cruising beneath the water in front of me, searching. The image immediately brought to mind the theme music from the movie Jaws. Woe to any small creature unaware of the danger lurking in the depths below.

A flash of white below the surface caught my eye. I looked more closely and recognized the light skin of a snapping turtle’s neck and forelegs. The mottled brown shell was covered with a green film of algae and its brown dinosaur-like tail blended into the bed of bladderwort it was suspended above. The turtle’s shell was twelve to fourteen inches long, a good-sized turtle for a small pond. It slowly began to swim, cruising beneath the water in front of me, searching. The image immediately brought to mind the theme music from the movie Jaws. Woe to any small creature unaware of the danger lurking in the depths below.

As I watched, a smaller snapping turtle swam into view from the other direction. The turtles seemed to notice each other and stopped, coming to rest on the bed of aquatic vegetation two feet apart. Cautiously they edged closer to each other. The small turtle’s shell was eight to nine inches long and appeared more confident as it approached the larger turtle. The other reacted by pulling its head back and retracting its neck inside its shell. I couldn’t determine if it was frightened by the small turtle’s approach or was calculating, waiting to strike at the intruder. They remained motionless, facing each other for several minutes, waiting for the other to move. A classic standoff if ever there was one.

The larger snapping turtle moved first. Slowly it extended its neck about an inch and stopped, as if testing to see how the smaller turtle would react. Suddenly, it lunged forward; its neck extended out its full length, and clamped its jaws on the flesh at the base of the neck and right leg. The small turtle thrashed in response and tried to get away as an air bubble escaped its mouth and floated to the surface. The large turtle looked like a reptilian version of a great white shark as it readjusted its grip and bit again. The struggle continued in slow motion, the large turtle sinking to the bottom of the pond while the small snapper tried to break free. It succeeded when the large snapping turtle tried to readjust its grip again. Once free, the small turtle quickly swam downward into the dense bed of bladderwort while the large one came to the surface. Two small nostrils at the end of its beak emerged above the water. It took a single breath and then sank below the surface once more, intent upon finding its smaller competitor. Meanwhile the small turtle wasted no time and used the distraction to camouflage and burrow itself so completely, that the large one cruised inches above it as the turtle continued its search. Slowly the turtle glided off into the dark waters, searching, until it finally disappeared.

The larger snapping turtle moved first. Slowly it extended its neck about an inch and stopped, as if testing to see how the smaller turtle would react. Suddenly, it lunged forward; its neck extended out its full length, and clamped its jaws on the flesh at the base of the neck and right leg. The small turtle thrashed in response and tried to get away as an air bubble escaped its mouth and floated to the surface. The large turtle looked like a reptilian version of a great white shark as it readjusted its grip and bit again. The struggle continued in slow motion, the large turtle sinking to the bottom of the pond while the small snapper tried to break free. It succeeded when the large snapping turtle tried to readjust its grip again. Once free, the small turtle quickly swam downward into the dense bed of bladderwort while the large one came to the surface. Two small nostrils at the end of its beak emerged above the water. It took a single breath and then sank below the surface once more, intent upon finding its smaller competitor. Meanwhile the small turtle wasted no time and used the distraction to camouflage and burrow itself so completely, that the large one cruised inches above it as the turtle continued its search. Slowly the turtle glided off into the dark waters, searching, until it finally disappeared.

Only then was I aware of the birdsong from the nearby brush, and the swallows in the field, as the rest of the world rushed in to reclaim the silence from the encounter moments ago.

A flash of white below the surface caught my eye. I looked more closely and recognized the light skin of a snapping turtle’s neck and forelegs. The mottled brown shell was covered with a green film of algae and its brown dinosaur-like tail blended into the bed of bladderwort it was suspended above. The turtle’s shell was twelve to fourteen inches long, a good-sized turtle for a small pond. It slowly began to swim, cruising beneath the water in front of me, searching. The image immediately brought to mind the theme music from the movie Jaws. Woe to any small creature unaware of the danger lurking in the depths below.

A flash of white below the surface caught my eye. I looked more closely and recognized the light skin of a snapping turtle’s neck and forelegs. The mottled brown shell was covered with a green film of algae and its brown dinosaur-like tail blended into the bed of bladderwort it was suspended above. The turtle’s shell was twelve to fourteen inches long, a good-sized turtle for a small pond. It slowly began to swim, cruising beneath the water in front of me, searching. The image immediately brought to mind the theme music from the movie Jaws. Woe to any small creature unaware of the danger lurking in the depths below. The larger snapping turtle moved first. Slowly it extended its neck about an inch and stopped, as if testing to see how the smaller turtle would react. Suddenly, it lunged forward; its neck extended out its full length, and clamped its jaws on the flesh at the base of the neck and right leg. The small turtle thrashed in response and tried to get away as an air bubble escaped its mouth and floated to the surface. The large turtle looked like a reptilian version of a great white shark as it readjusted its grip and bit again. The struggle continued in slow motion, the large turtle sinking to the bottom of the pond while the small snapper tried to break free. It succeeded when the large snapping turtle tried to readjust its grip again. Once free, the small turtle quickly swam downward into the dense bed of bladderwort while the large one came to the surface. Two small nostrils at the end of its beak emerged above the water. It took a single breath and then sank below the surface once more, intent upon finding its smaller competitor. Meanwhile the small turtle wasted no time and used the distraction to camouflage and burrow itself so completely, that the large one cruised inches above it as the turtle continued its search. Slowly the turtle glided off into the dark waters, searching, until it finally disappeared.

The larger snapping turtle moved first. Slowly it extended its neck about an inch and stopped, as if testing to see how the smaller turtle would react. Suddenly, it lunged forward; its neck extended out its full length, and clamped its jaws on the flesh at the base of the neck and right leg. The small turtle thrashed in response and tried to get away as an air bubble escaped its mouth and floated to the surface. The large turtle looked like a reptilian version of a great white shark as it readjusted its grip and bit again. The struggle continued in slow motion, the large turtle sinking to the bottom of the pond while the small snapper tried to break free. It succeeded when the large snapping turtle tried to readjust its grip again. Once free, the small turtle quickly swam downward into the dense bed of bladderwort while the large one came to the surface. Two small nostrils at the end of its beak emerged above the water. It took a single breath and then sank below the surface once more, intent upon finding its smaller competitor. Meanwhile the small turtle wasted no time and used the distraction to camouflage and burrow itself so completely, that the large one cruised inches above it as the turtle continued its search. Slowly the turtle glided off into the dark waters, searching, until it finally disappeared.